While looking up information and people's thoughts on Gunda, I came across this blog that has a fictional interview with director Kanti Shah. This is a lot funnier if you actually watch the film first haha

You can find the post here

http://greatbong.net/2007/06/20/gunda-the-legend/

Or for the uninitiated:

[This very long blogpost is a transcript of an interview with the great director Kanti Shah, director of the legendary Mithun-da movie "Gunda". And yes this interview is a work of fiction: it has no resemblance to any person---living or dead or seriously sick. I also have no connection with Kanti Shah or the production house of Gunda. ]

“There are two kinds of people in the world. Those who have seen “Gunda”. And those who shall see it.” ——Roger Abhert

Interviewer: Let’s get right to that age-old question fans and critics ask the moment they step out of the theatres—why? What made you make Gunda?

KS: The mid 90s were marked by great intellectual ferment and socio-political change in India. With unbridled economic liberalisation strengthening the unholy cabal of politicians and moneyed ruffians (I refer to this in Gunda as “aaj gundagiri aur netagiri dono eki baap ke do harami aulaad hain) , the nation witnessed fundamental transformations —a fact that was being systematically overlooked by popular escapist entertainment which minted money through vacuous NRI romances, forgetting its solemn duty to be the mirror of its times.

In 1997, I sought to make a statement through “Loha” where I tried to weld together the pernicious effects on the fabric of India of the new media (Inspector Kale, the evil policeman whenever he is asked to counter crime says “Main jayoon, Zee TV dekhne?”), caste (”driver ki ladki itni sexy!“), the fondling of a man’s bottom by another man (”mawali log tujhe chikna chikna bolke tere peechwar-e pe haath pherte the“) and existential angst (”Abh main bin petrol ki gari aur bin nashe ke tari hoon, main woh phateli sari hoon jo ek hijra bhi naheen pahenegi” ). However, because of the demands of the producer we had to put in a totally unrelated Govinda- Monisha romance angle that destroyed the celluloid mosaic I had intended “Loha” to be. Taking the lesson that even moderately big budgets require you to sell your artistic soul, I decided to make Gunda (derived from the German “Gund” meaning war and which some etymologists claim has been formed by the insertion of the word “Lund” into the word “Gaand” making it “G+ und”) by myself on a shoe-string budget, determined not to compromise my creativity in any manner.

Interviewer: Certain critics consider Gunda to represent the very worst of everything Bollywood has to offer. A done-to-death revenge plot, gratuitous violence especially towards women, shocking language and over-the-top acting. How do you react to that criticism?

KS: These critics are unfortunately literalists. And while they applaud the surreal appeal of Fellini’s La Strada, they are unwilling to put away their neorealist sensibilities while evaluating Gunda. My movie, intentionally confined by the grammar of popular cinema so as to make the message accessible to the hoi polloi, is actually an allegory where each villain represents something larger than just himself. More specifically, each villain here is a metaphor for the challenges facing India in the 90s.

Let me e xplain.

xplain.

xplain.

xplain.First there is Bulla, the main evil man. His motto is “Mera naam hain Bulla, rakhta hoon main khullaaaaaa“. While the literalists interpret this as a declaration that this man does not wear underwear, most right-thinking viewers will immediately realize that Bulla represents the “open” economy—that instrument of the capitalist West to suck out the life blood from the unwashed masses. Yes Bulla’s malignancy represents the depredations wrought by the “khullam-khulla capitalist system” with its removal of protection for farmers and small industries: in short the principal villain of the 90s.

Next there is Chutiya, Bulla’s hermaphrodite brother who is kept alive through a steady supply of “London se sex ki goliyan” in the hope that he becomes a “mard” or man. Chutiya represents the confused generation of the 90s, neutered morally at birth and slowly converted into a perverted abomination by the erotic media images from MTV and Channel V (the sex ki goliyan).

Next there is Chutiya, Bulla’s hermaphrodite brother who is kept alive through a steady supply of “London se sex ki goliyan” in the hope that he becomes a “mard” or man. Chutiya represents the confused generation of the 90s, neutered morally at birth and slowly converted into a perverted abomination by the erotic media images from MTV and Channel V (the sex ki goliyan).Then there is Pote—jo aapne baap ki bhi naheen hote. He represents those who revel in wanton violence ; whose raiso n d’etre for living is in inflicting pain and suffering—-kind of like those who took the lead during the Babri Masjid riots and later in Gujrat. And their life philosophy is articulated by Pote when he declares, with barely controlled glee that: “Hum aise lashein bicha denge jaise kisi nanhen munhen bacche ke nunhi se pesaab tapakta hain…tap tap“. When the sound of dead bodies falling on the ground resonates like the pitter-patter of an innocent baby’s urine striking the cobble stones—you know that the country is in trouble.

n d’etre for living is in inflicting pain and suffering—-kind of like those who took the lead during the Babri Masjid riots and later in Gujrat. And their life philosophy is articulated by Pote when he declares, with barely controlled glee that: “Hum aise lashein bicha denge jaise kisi nanhen munhen bacche ke nunhi se pesaab tapakta hain…tap tap“. When the sound of dead bodies falling on the ground resonates like the pitter-patter of an innocent baby’s urine striking the cobble stones—you know that the country is in trouble.

n d’etre for living is in inflicting pain and suffering—-kind of like those who took the lead during the Babri Masjid riots and later in Gujrat. And their life philosophy is articulated by Pote when he declares, with barely controlled glee that: “Hum aise lashein bicha denge jaise kisi nanhen munhen bacche ke nunhi se pesaab tapakta hain…tap tap“. When the sound of dead bodies falling on the ground resonates like the pitter-patter of an innocent baby’s urine striking the cobble stones—you know that the country is in trouble.

n d’etre for living is in inflicting pain and suffering—-kind of like those who took the lead during the Babri Masjid riots and later in Gujrat. And their life philosophy is articulated by Pote when he declares, with barely controlled glee that: “Hum aise lashein bicha denge jaise kisi nanhen munhen bacche ke nunhi se pesaab tapakta hain…tap tap“. When the sound of dead bodies falling on the ground resonates like the pitter-patter of an innocent baby’s urine striking the cobble stones—you know that the country is in trouble.The 90s were marked by greedy industrialists, servants of pure avarice, who made common men kneel down and suck their bananas while they aggrandized themselves. This class is crystallized in the character of Ibu Hatela whose patented introduction is “Mera  naam Ibu Hatela, Ma meri chudail ki beti, baap mera shaitan ka chela, khayega kela?” Their natural proclivity to go through the backdoor of the economic system is expressed through Ibu Hatela’s repeated use of lines like “Hum uske pantloon pharenge. Woh bhi peeche se”

naam Ibu Hatela, Ma meri chudail ki beti, baap mera shaitan ka chela, khayega kela?” Their natural proclivity to go through the backdoor of the economic system is expressed through Ibu Hatela’s repeated use of lines like “Hum uske pantloon pharenge. Woh bhi peeche se”

naam Ibu Hatela, Ma meri chudail ki beti, baap mera shaitan ka chela, khayega kela?” Their natural proclivity to go through the backdoor of the economic system is expressed through Ibu Hatela’s repeated use of lines like “Hum uske pantloon pharenge. Woh bhi peeche se”

naam Ibu Hatela, Ma meri chudail ki beti, baap mera shaitan ka chela, khayega kela?” Their natural proclivity to go through the backdoor of the economic system is expressed through Ibu Hatela’s repeated use of lines like “Hum uske pantloon pharenge. Woh bhi peeche se”And of course the law, as represented by Inspector Kale ,(a bit of Quentin-ish self-reference here as the cop in Loha also had the same name) had by the 90s become an extension of the criminal system. This is conveyed, without pulling any punches, in the scene where an honest policeman (the hero’s father) accuses Kale of being hand-in-glove with the criminals through the poetic denouncement: “Lagta haain Bulla ka thukh chata hain tumhe, peshaab piya hain uska“. Licking spit and drinking urine. Verily that was the law then.

policeman (the hero’s father) accuses Kale of being hand-in-glove with the criminals through the poetic denouncement: “Lagta haain Bulla ka thukh chata hain tumhe, peshaab piya hain uska“. Licking spit and drinking urine. Verily that was the law then.

policeman (the hero’s father) accuses Kale of being hand-in-glove with the criminals through the poetic denouncement: “Lagta haain Bulla ka thukh chata hain tumhe, peshaab piya hain uska“. Licking spit and drinking urine. Verily that was the law then.

policeman (the hero’s father) accuses Kale of being hand-in-glove with the criminals through the poetic denouncement: “Lagta haain Bulla ka thukh chata hain tumhe, peshaab piya hain uska“. Licking spit and drinking urine. Verily that was the law then.Finally the Delhi politician “kafan chor neta” (Dilli se billi ka dudh peeke aaya hain) and Bacchu Bagona represent the cancerous Indian political leadership where friendships based on mutual benefit (teri biwi uske paas aur uske biwi tera paas soti thi) and not ideology are quickly transformed into enmity based on the shifting alliances of the criminals that control the politicians and are in turn provided protection by these lumpen administrative  elements (as Chutiya says: “Yeh jo kaala genda hain na iske saath jhagra mat kijiye. Kyon ke kanoon aur humare beech Yeh ek saafed chadar hain. Iske saath jhagra karenge na to kapde dhulenge bharatiyon addon pe”)

elements (as Chutiya says: “Yeh jo kaala genda hain na iske saath jhagra mat kijiye. Kyon ke kanoon aur humare beech Yeh ek saafed chadar hain. Iske saath jhagra karenge na to kapde dhulenge bharatiyon addon pe”)

elements (as Chutiya says: “Yeh jo kaala genda hain na iske saath jhagra mat kijiye. Kyon ke kanoon aur humare beech Yeh ek saafed chadar hain. Iske saath jhagra karenge na to kapde dhulenge bharatiyon addon pe”)

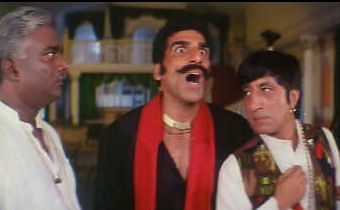

elements (as Chutiya says: “Yeh jo kaala genda hain na iske saath jhagra mat kijiye. Kyon ke kanoon aur humare beech Yeh ek saafed chadar hain. Iske saath jhagra karenge na to kapde dhulenge bharatiyon addon pe”)Having created these personifications of India’s problems, I also created as their dramatic adversary (Main hoon jurm se nafrat karne waala, shareefon ke liye jyoti, goondon ke liye jwaala) the character of Shankar, (played by Prabhuji Mithun Chakraborty) a coolie in a airport . He represents the typical hard-working Indian man forced to balance time between an overweight girl friend, an even fatter sister, an  overacting father, alcoholic friends and a pet monkey who can drive a car. It is Shankar and his family that is crushed underneath the “system” of the 90s—a system that Shankar rises against through the inspirational “Do chaar chaaye aat dus. Bus” reciting of even numbers and concomitant retributory cleansing violence.

overacting father, alcoholic friends and a pet monkey who can drive a car. It is Shankar and his family that is crushed underneath the “system” of the 90s—a system that Shankar rises against through the inspirational “Do chaar chaaye aat dus. Bus” reciting of even numbers and concomitant retributory cleansing violence.

overacting father, alcoholic friends and a pet monkey who can drive a car. It is Shankar and his family that is crushed underneath the “system” of the 90s—a system that Shankar rises against through the inspirational “Do chaar chaaye aat dus. Bus” reciting of even numbers and concomitant retributory cleansing violence.

overacting father, alcoholic friends and a pet monkey who can drive a car. It is Shankar and his family that is crushed underneath the “system” of the 90s—a system that Shankar rises against through the inspirational “Do chaar chaaye aat dus. Bus” reciting of even numbers and concomitant retributory cleansing violence.Thus being a depiction of the eternal conflict between good and evil with each character being an anthropomorphization of historical forces, Gunda transcends all cinematic formulae. Even after this if people want to call Gunda trite, well all I can say, paraphrasing a line from Loha, that their intellects “kisi  garbabhati billi ki latakti hui pet ki tarah latak raha hain”

garbabhati billi ki latakti hui pet ki tarah latak raha hain”

garbabhati billi ki latakti hui pet ki tarah latak raha hain”

garbabhati billi ki latakti hui pet ki tarah latak raha hain”Interviewer: Kind of like a Mahabharata of the times.

KS: Exactly. And like Mahabharata, Gunda is not just about conflict. I will go so far as to say that the conflict is secondary to the human drama. In the best traditions of a Greek tragedy, noone comes unscathed from the Gunda experience. While ostensibly the story of a man who loses his father, sister and wife to the evils of society, it is also the cautionary tale of an evil man (Bulla) who swept away in a malestorm of revenge and violence (as he once tells Shankar: “Tujhe jalta bhunta dekhkar hum is tarah khush hote hain jis tarah koi shaitani-type ke bacchen aapne guriya ke haath payer todkar talee marte hainnnnnnn”) is consumed by the flames of his own rage.

He first sees his darling sister made “lamba” by arch-rival Lambu Atta following which Bulla laments, in an epic scene, “Munni meri behen munni, munni meri behen munni, to tu mar gyee? Lambu ne tujhe lamba kar diya? Maachis ki tili ko khamba kar diya?“. And then the pain he experiences everyday in seeing his mentally challenged younger brother trying to become a “mard” is gut-wrenching. Bulla feeds him sex pills from London and like a kind elder brother provides him girls to rape (and I should add, Chutiya doesnt even know it’s a crime to forcibly fornicate as he keeps asking Bullah: “Bhaiyya bhaiyya, rape karna kya buree baat hain?“). Till one day Chutiya emerges a man —an occasion he marks by disco-dancing with eunuchs to the tune of “Haye haye mere bhai jawaan ho gya, toota hua teer kaman ho gya“. And yet just when “tere tube main light aaya tha” , Shankar despatches Chutiya to his maker (as Bulla says: “tera fuse uda diya”) by cutting off his organ. (Incidentally that castration scene was tough to picturize—-many crew members got reacquainted with last night’s dinner !). What tragedy!

gut-wrenching. Bulla feeds him sex pills from London and like a kind elder brother provides him girls to rape (and I should add, Chutiya doesnt even know it’s a crime to forcibly fornicate as he keeps asking Bullah: “Bhaiyya bhaiyya, rape karna kya buree baat hain?“). Till one day Chutiya emerges a man —an occasion he marks by disco-dancing with eunuchs to the tune of “Haye haye mere bhai jawaan ho gya, toota hua teer kaman ho gya“. And yet just when “tere tube main light aaya tha” , Shankar despatches Chutiya to his maker (as Bulla says: “tera fuse uda diya”) by cutting off his organ. (Incidentally that castration scene was tough to picturize—-many crew members got reacquainted with last night’s dinner !). What tragedy!

gut-wrenching. Bulla feeds him sex pills from London and like a kind elder brother provides him girls to rape (and I should add, Chutiya doesnt even know it’s a crime to forcibly fornicate as he keeps asking Bullah: “Bhaiyya bhaiyya, rape karna kya buree baat hain?“). Till one day Chutiya emerges a man —an occasion he marks by disco-dancing with eunuchs to the tune of “Haye haye mere bhai jawaan ho gya, toota hua teer kaman ho gya“. And yet just when “tere tube main light aaya tha” , Shankar despatches Chutiya to his maker (as Bulla says: “tera fuse uda diya”) by cutting off his organ. (Incidentally that castration scene was tough to picturize—-many crew members got reacquainted with last night’s dinner !). What tragedy!

gut-wrenching. Bulla feeds him sex pills from London and like a kind elder brother provides him girls to rape (and I should add, Chutiya doesnt even know it’s a crime to forcibly fornicate as he keeps asking Bullah: “Bhaiyya bhaiyya, rape karna kya buree baat hain?“). Till one day Chutiya emerges a man —an occasion he marks by disco-dancing with eunuchs to the tune of “Haye haye mere bhai jawaan ho gya, toota hua teer kaman ho gya“. And yet just when “tere tube main light aaya tha” , Shankar despatches Chutiya to his maker (as Bulla says: “tera fuse uda diya”) by cutting off his organ. (Incidentally that castration scene was tough to picturize—-many crew members got reacquainted with last night’s dinner !). What tragedy! Does Gunda’s scope end here? No sir. The canvass is even larger. Sin and redemption. Shankar risks his life for sworn enemy Bulla’s illegitimate daughter (”Haseena ka paseena”). But forgiveness is not for all. At the opposite end, arch-criminal Lambu Atta, asks in vain for mercy from Bulla once he realizes that he is surrounded by Bulla’s deadly assassins.

Does Gunda’s scope end here? No sir. The canvass is even larger. Sin and redemption. Shankar risks his life for sworn enemy Bulla’s illegitimate daughter (”Haseena ka paseena”). But forgiveness is not for all. At the opposite end, arch-criminal Lambu Atta, asks in vain for mercy from Bulla once he realizes that he is surrounded by Bulla’s deadly assassins.Bulla. mere ko mat maar. Mere ko aapna bhadwa bana de. Main ladkiyan supply karte rahoonga aur tu maaze lete rahena. Tere ko AIDS se bachane ke liye nirodh ban jayoonga. Towel baanke tere kamad se lapak jayoonga. Mere ko mat maar. Aur agar maarna hi hain to mujhe cheel-chaal ke chakka bana de. Main sari lapet kar tere liye dance karoonga…Gore gore gaal gaal gore gore..

And no. Even this offer of slavery cannot save Lambu Atta who gets his “maut ka chata”.

Interviewer: One of the persistent criticisms of “Gunda” made by feminists and even by some masculinists is that Gunda is a monument to misogyny and chauvinism. They have taken umbrage to the lines :” Roti hote hain khane ke liye aur boti hote hain chabane ke liye, badhsha ki behen ho, ya fakeer ki beti, har kisi ko aana parta marad ke niche bajane ke liye citi” and “Chatri hotee hain kholne ke liye, chadar hotee hain orne ke liye aur ladki hotee hain cherne ke liye” as being medieval and repugnant. Comments.

KS: There it is again: the trap of literalism. In “Gunda” women represent purity and honesty and what I show is the violation of that. Simple. I never want to titillate, I can assure you. In fact where Bulla encounters Shankar’s wife, they talk in perfect rhyme to each other—which attests to the fact that my intention is to be poetic, rather than vulgar.

KS: Now here’s my question to you, the interviewer. As a fan yourself, what is your favourite Gunda moment?

KS: Now here’s my question to you, the interviewer. As a fan yourself, what is your favourite Gunda moment?Interviewer: Tables turned. Haha. Well there is a scene in which super-pimp Lucky Chikna screams at a sex-worker who is doing “liptam chipti chipkam lipti” with a guy instead of servicing her client. When she protests that “Woh buddha kuch karta naheen hain. Sirf bolta hain choos choos meri ungli choos“, Lucky Chikna delivers the line:”Dhande pe baithi hain to buddha kya, jawan kya, kya chotha kya bara, kya baitha kya khara“. There is any austere beauty in this scene I have never been quiet able to fathom.

Interviewer: Now back to the questions. What do you think is the legacy of Gunda?

KS: Gunda is on IMDB at 8.6. It is uniformly accepted as a masterpiece. It holds the world record for being screened in almost all men’s hostels in India. Often in a loop. There is are orkut communities for it. There is even a fan site. It is now a popular baby-name. There is a city in the republic of Buryatia named after the movie. A Gunda-themed apparel line exists. There is “Gunda pickle” which on consumption makes you scream like Lambu Atta after he sees his chikna bhai Kundan murdered. An Aussie band has named themselves Gunda Guys to honor their love for the classics. The Zulus have named a “cottol reel car” Gunda Gunda.

KS: Gunda is on IMDB at 8.6. It is uniformly accepted as a masterpiece. It holds the world record for being screened in almost all men’s hostels in India. Often in a loop. There is are orkut communities for it. There is even a fan site. It is now a popular baby-name. There is a city in the republic of Buryatia named after the movie. A Gunda-themed apparel line exists. There is “Gunda pickle” which on consumption makes you scream like Lambu Atta after he sees his chikna bhai Kundan murdered. An Aussie band has named themselves Gunda Guys to honor their love for the classics. The Zulus have named a “cottol reel car” Gunda Gunda.Gunda dialogues have passed into popular lingo. “Tere behen ko kar doonga khullam khullah” is an accepted form of greeting between men in college campuses in India. The idea of Lucky Chikna’s sex garden (”latakta circus”) where people fornicated on hanging khatiyas has been adopted by discerning brothels all over the world. Many children born accidentally due to defective contraceptives are being named “Nirodh Kumar” in many parts of India, in honour of a character of the same name in “Gunda”.

Interviewer: Lastly, there are so many questions over which fans have agonized over the years. Why does the hero’s father’s moustache disappear and reappear between scenes? Why does the Mithun-da character, a coolie, have a cellphone in the mid 90s? And also a rocket-launcher? Why does 70% of the movie take place on a tarmac? Is the relationship between Bulla and Lambu Atta homoerotic (as Lambu says: Bulla ke naam leke tune khara kar diya hain mera) ?Why did Chutiya think that the bathroom is the only place Shankar will not look for him? Are the Ambassadors in the movie remote-controlled?Why is the Vidhan Sabha and the High Court the same building?Why…

KS: (interrupting). Yes I know. Some true fans have tried to find the solution to these questions through the Gunda FAQ. All I can say is that I was greatly influenced byDadaism, a movement of the early 1900s whose principle was the conscious rejection of logic, rationality and conventional aesthetics. Actually the name Bulla is a tribute to Bulldada which means something that is “brilliant specially because it does not know its own stupidity”, with Bulldada itself a term born out of the Dadaist philosophy. In short, with such influences,trying to find total coherence in Gunda is ultimately a self-defeating experience.

KS: (interrupting). Yes I know. Some true fans have tried to find the solution to these questions through the Gunda FAQ. All I can say is that I was greatly influenced byDadaism, a movement of the early 1900s whose principle was the conscious rejection of logic, rationality and conventional aesthetics. Actually the name Bulla is a tribute to Bulldada which means something that is “brilliant specially because it does not know its own stupidity”, with Bulldada itself a term born out of the Dadaist philosophy. In short, with such influences,trying to find total coherence in Gunda is ultimately a self-defeating experience.Interviewer: Any final words to the fans?

KS: Thank you for the love and support. And watch Gunda. Again and again. There has never been a movie like this before. Trust me. There never will be one like this again.

[Acknowledgements: Gunda movie online, and the orkut Gunda community and its active members for the inspiration]

No comments:

Post a Comment